Who can forget James Cameron’s movie The Abyss!

Who can forget James Cameron’s movie The Abyss!

If I need to remind you, Cameron is the creator of Avatar.

The Abyss was an imaginative movie of the 1980s, where the plot concerned commercial divers who had been hired by the Navy to assist with the salvage of a nuclear submarine. It involved very deep diving, and special technology that actually has some basis in fact.

By far the most memorable part of the movie involves a diving helmet filled with a liquid that the diver, with some trepidation, breathed.

Below is a clip from the movie that demonstrated, quite dramatically, and with a live animal, the concept of liquid breathing.

It’s not a trick – it really works, on small rodents.

In the 1960s and 70s the Office of Navy Research funded basic research at Duke University on liquid breathing, with Dr. Johannes A. Kylstra as the lead scientist on the project. After proving the technique worked on rodents and dogs, it progressed to the point of having a commercial diver, Frank Falejczyk, become the first person to breathe oxygenated liquid.

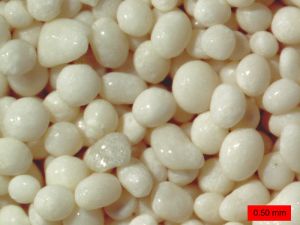

First, Frank inhaled well-oxygenated saline on an operating table. Unfortunately, extraction of the liquid from his lung did not work as planned. He developed pneumonia as a result of the exposure. But eventually, the researchers found that oxygenated perfluorocarbons could be tolerated by the lung, and could, at least in animals, allow the extraction of dissolved oxygen for a period of time without ill effects.

Eventually, Falejczyk made a presentation on his trials to an audience that happened to include James Cameron. Apparently, Cameron was impressed.

So, can man breathe liquid and not drown? At least one retired physician says yes. Arnold Lande, a retired American heart and lung surgeon, has patented a scuba suit that would, he suggests, allow a human to breathe oxygenated liquid.

Now, making such a device work is in fact a tall order. Although Kylstra’s animal experiments showed that rodents and even dogs could be ventilated for up to an hour, the limiting factor seemed to be the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the body. The perfluorocarbons gave up their stored oxygen readily, but did not adequately eliminate carbon dioxide.

That is a major problem.

In the 1980s an Israeli colleague and I conducted biomedical research on potential Navy applications of high frequency ventilation (HFV), an unusual method of mechanical ventilation that now has many clinical applications. It soon occurred to me that appropriate frequencies applied to the mouth or chest wall could greatly accelerate the diffusion of carbon dioxide in liquid, just as it did in air. However, I never proposed studying liquid ventilation, and if I had, the proposal would likely have been rejected almost immediately on the basis of Frank Falejczyk’s bad outcome.

Dr. Lande has proposed solving the carbon dioxide retention problem by tieing artificial gills straight into the human circulatory system. There are obvious safety concerns with such a plan, but if those concerns could be engineered out, there is still the problem of creating working gills with enough throughput to eliminate CO2 from a working diver.

I once witnessed a demonstration of an artificial gill, conducted in front of several well-educated Navy diving physicians and scientists. After descending about three feet down into a pool, the “inventor” lay motionless for 30 seconds, then bounded up out of the water, breathlessly saying, “Basically, it works.”

His panted words were not convincing.

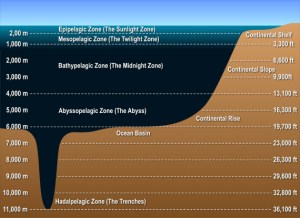

Based on fairly recent history, and the fact that for deep diving, not one lung but both lungs would have to be completely filled with perfluorocarbon or similar liquid, it seems that a practical and safe liquid breathing system will be a huge engineering challenge. I can envision ways that it could be done, but at what cost, and for what purpose?

I am mindful, being an aviator, that such questions were not allowed to stymie Wilbur and Orville Wright. However, these days, human experimentation involving the complete filling of human lungs would face a formidable hurdle, called the Human Use Committee. In the U.S. at least, a repeat of Kylstra’s experiments is very unlikely to be approved by Research Ethics committees.

But could it happen in other countries with lessor human research safeguards?

Time will tell.