Shortly before Howard Hughes’ massive ship, the Glomar Explorer, conducted a secret mission to recover a sunken Soviet submarine in the Pacific, under the guise of collecting manganese nodules, a much smaller Research Vessel was collecting the real thing, on the Blake Plateau about 150 miles southeast of the Georgia-Florida Coast .

Shortly before Howard Hughes’ massive ship, the Glomar Explorer, conducted a secret mission to recover a sunken Soviet submarine in the Pacific, under the guise of collecting manganese nodules, a much smaller Research Vessel was collecting the real thing, on the Blake Plateau about 150 miles southeast of the Georgia-Florida Coast .

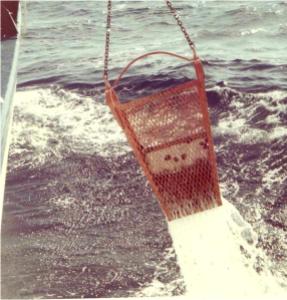

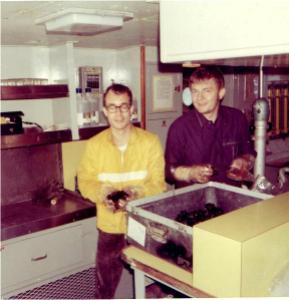

In 1970 I was the only biologist on board the Duke University’s Research Vessel, the R.V. Eastward. Also present were geologists from the Lamont Geological Observatory, and a geologist, Dr. J. Helmut Reuter, from Georgia Tech where I was in graduate school.

There is a wealth of information on the association between bacteria and ferromanganese nodules, with some scientists convinced that bacteria precipitate manganese out of solution in seawater, thus leading to nodule creation. Arguably, the best reference on this subject is the book Geomicrobiology by H.L. Ehrlich and D.K. Newman (5th ed. 2009)

My mentors at Georgia Tech and I knew bacteria would be found coating the outside of the nodules, but we wanted to know if viable bacteria remained inside the nodules once surface contamination had been removed. My mission onboard the R.V. Eastward was to setup a small bacteriological laboratory and then search for that evidence.

Ultimately, our search was not successful. No viable bacteria were cultured.

But that is the nature of science — you don’t know until you try.

Success or not, how do scientists celebrate the end of a cruise to the Blake Plateau? Well in Nassau celebration involves fine German Beer and even finer Cuban Matasulem Rum. Yes, at the time Matasulem Rum still bearing its Cuban label could be found in the Bahamas.

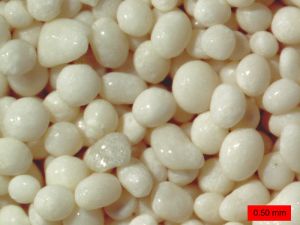

Factoid for the day: Since Helmut Reuter was a geologist, he taught me that the sand around Nassau, unbelievably soft on your feet, was called oolitic sand.

Forty years later what do we know about these curious nodules? For one thing, they are extremely slow growing, growing about a centimeter over several million years. That means the nodules in my possession are on the order of 12 million years old.

Secondly, although scientists are stimulated by the competition to discover the one correct theory among numerous hypotheses for the origin of something mysterious, such as manganese nodules, in this a case it looks like virtually everyone was correct. Nodules seem to form from precipitation of metals from seawater, especially from volcanic thermal vents, the decomposition of basalt by seawater and the precipitation of metal hydroxides through the activity of various manganese fixing bacteria. For any given nodule field, these chemical and biological processes may have been working simultaneously, or sequentially. For any one nodule, it is presently impossible to tell which processes affected its formation.

We should realize as we hold a 12 million year old rock in our hand, that it is far too much to expect to know details of its history over eons of time.