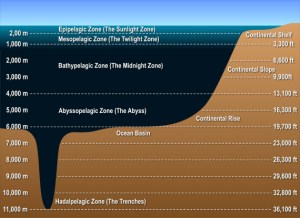

The Puerto Rico Trench is the deepest part of the Atlantic Ocean, and is only surpassed in its depth by the Marianas Trench in the Pacific Ocean. It is 500 miles long, and at its deepest plummets 28,232 feet down.

After receiving my doctorate with a special interest in deep-sea physiology, I was invited on board the oceanographic Research Vessel (RV) Gilliss for an expedition to the Puerto Rico Trench. I was accompanied on that research cruise by Dr. Robert Y. George, a deep-sea biological oceanographer from Florida State University.

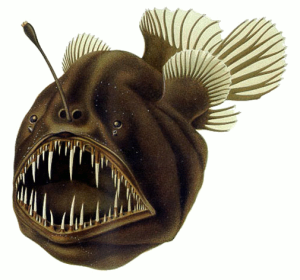

I had been studying the effect of very high pressure on invertebrate hearts. As luck would have it, the largest population of deep-sea creatures indigenous to the deepest places in the ocean are invertebrates (animals lacking vertebrae, backbones.) But on the way down to the deepest reaches of the trench, you encounter some very strange creatures indeed, such as the Humpback Angler Fish.

These bizarre and frightening looking fish inhabit the abyssal pelagic zone (or the Abyss) between 13,000 and 20,000 feet. But below the water containing these abyssal fish lies the zone of the deep trenches, the hadalpelagic zone between 20,000 and 36,000 feet, the deepest point in any ocean.

“Denizens of the Deep” are known in merfolk tradition as the beasts that swallow up the sun at the end of the day, which is somewhat ironic since sunlight never reaches down to the abyssal and hadal zones. Whatever light is there, is produced by bioluminescence. Down there, light means either a meal, or a trap. And since meals are uncommon in the sparsely populated ocean depths, predators seem designed to ensure they miss no opportunities to feed. Their jaws, fangs, and other anatomical structures seem especially designed to snag a hapless passer-by, and provide no chance of escape for those caught. Fortunately for us, animals adapted to the high pressure, low oxygen environment of the deep ocean cannot survive in shallow waters.

But imagine for a moment that something perturbed that natural order. Time has separated us from man-eating dinosaurs, but the only thing separating us from deep-sea monsters, ferocious predators that make piranhas look playful, is something as simple as pressure and oxygen. Could things change?

Well, not to scare you, but until 1983 or so, the Puerto Rico Trench was a huge pharmaceutical dumping ground. Massive quantities of steroids and antibiotics, and chemicals capable of causing genetic mutations, came to rest on the sea floor, or were dispersed in the waters above and around the trench.

Read more about that here: http://deepseanews.com/2008/04/dumping-pharmaceutical-waste-in-the-deep-sea/

You don’t need to take just one person’s word for it. Professor R.Y. George himself commented on the issue in his resumé.

July 5 – July 30, 1977. Revisited Puerto Rico Trench (now Pharmaceutical Dump Site) aboard R/V GILLISS of the University of Miami to study Barophylic (pressure-loving)bacteria (Dr. Jody Demming’s Ph. D. work from Dr. Rita Colwell’s Lab. in the University of Maryland), and to study meiofauna, macrofauna and megafauna (in collaboration with Dr. Robert Higgins of the Smithsonian Institution).

Frankly, if I was visiting Puerto Rico, and signed up for a deep-sea fishing trip, I’d ask the boat captain just how deep we’d be fishing. I really wouldn’t want to bring up a Humpback Angler Fish large enough to eat the boat. After all, Angler Fish are fishermen too.

For a NOAA sponsored animated tour of the Trench, play the following high resolution video.

[youtube id=”v1OnsuyFdaM” w=”700″ h=”600″]