Every fall I look forward to the current of Monarch Butterflies coursing their way across our local roads and beaches in Panama City Beach, FL, searching for one last refueling stop before heading out across the Gulf of Mexico to overseas destinations. They know where they are going en masse, so casually it seems, not in the least concerned about the doubtful safety of single engine flight over vast stretches of unforgiving water.

Every fall I look forward to the current of Monarch Butterflies coursing their way across our local roads and beaches in Panama City Beach, FL, searching for one last refueling stop before heading out across the Gulf of Mexico to overseas destinations. They know where they are going en masse, so casually it seems, not in the least concerned about the doubtful safety of single engine flight over vast stretches of unforgiving water.

While over land, most fly low, at human shoulder height, perhaps looking for food. It makes for an almost magical walk outside — continuously being passed by little animated flying machines. When crossing roads, most of the migrating butterflies, but not all, climb to safer altitudes, and increase their speed. I like to think that strategy is deliberate, but it could in fact be nothing more than the effects of buffeting by the wake of passing cars. Nevertheless, their success rate at crossing roads seems to be better than that of squirrels, which are arguably larger-brained animals. But then squirrels are dare-devils, not aviators.

I have walked to the water’s edge, watching how the little aviators behave as they approach the beginning of their long leg over water. They do not hesitate, but fling themselves forward into whatever awaits them.

Whenever I witness this sight I want to cheer them on, like Americans must have cheered Lindbergh as he set off across the Atlantic for the first time. It seems like folly for them to attempt such a journey, but amazingly, millions of them make that transit every year.

The scene during their return in the spring is even more emotional. Walking on the beach at that time, you see the surf washing in the numerous bodies of those aviators who almost made it, reminiscent of the beaches at Normandy. And like the scenes of war, dragonflies lie in wait at the water’s edge attacking the weakened Monarchs soon as they cross over the relative safety of land.

I have been so infuriated at the sight of such wanton attacks that once I chased a heavily laden dragonfly with a Monarch in its grasp, and caused the little Messerschmitt to release its prey.

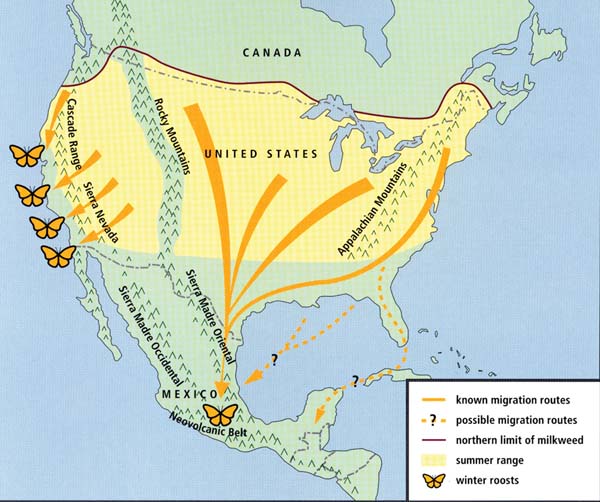

The Monarch I saved did not thank-me by landing on my shoulder to take a breather. It was too dangerous to stop, and it had places to go, places far away from the sea, driven by a genetic memory of fields of milkweed.

Oddly enough, experts seem unsure as to whether there is actually a migratory flyway from the Panama City area to Mexico, the over-wintering grounds for most Monarchs. To me the answer is obvious; even though the flight of roughly 800 miles over water with no place to feed is almost unimaginable. The little aviators make that trip, spring and fall, as proven by the millions of orange and black-rayed butterflies crossing the white sand shores of the Gulf of Mexico, and by the surf-washed bodies of those brave aviators who died in the attempt.